Although I have may projects currently working through the system there is always room for one more and this week, given how cold it is and in some parts snowy, it seems the ideal time to start sharing with you my plans for an N Scale Union Pacific rotary snow plow.

This project is at the request of a fellow modeller but it’s one I have been thinking about for a while for myself, I think the rotarys are just fantastic!

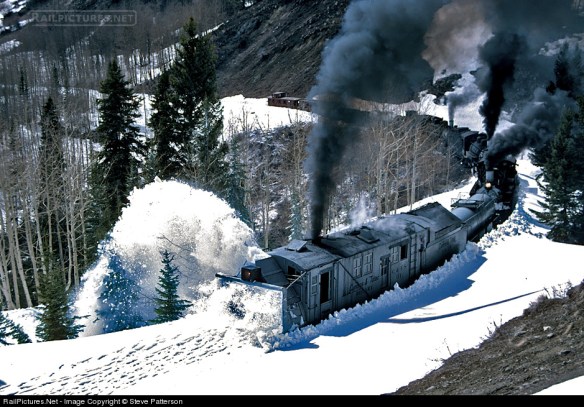

So what are rotary snow plows? In short they’re the last line of defense against heavy snow fall; when the snow’s falling and regular plows and shovels simply can’t do it the rotarys are called out to cut their way through. And they do literally cut their way through. In the image below, taken by Steve Patterson and displayed on Railpictures you can see ex-DRGW steam rotary ‘OY’ being pushed by three steam locomotives.

The photo caption says: ‘In an attempt to open its line from winter snows, Cumbres & Toltec Scenic operated a triple-header rotary snow plow train on May 3, 1997. Three mikados are shoving Rotary OY as they near the deepest snow encountered on Windy Point, Colo., just short of the summit at Cumbres Pass which wouldn’t be achieved until the next day. The footprints in the snow ahead of the rotary are from pursuing photographers.’

Regular snow plows work by forcing the show aside and for the majority of areas this is just fine. In winter months you can often see plows fitted to regular locomotives as with UP 9564 in the photo below. (Picture from Home Town by Handlebar).

But when it gets a bit deeper the plow has nowhere to push the snow so it needs to be lifted above. This can be done with a larger dedicated plow which is pushed by locomotives as shown below. (Photo by Kevin Burkholder and displayed on Railpictures).

The large ‘scoop’ at the front pushes the snow up and out to the sides, the ‘wings’ (behind the plow with VB 103 marked on the side) can be adjusted to push the snow even further, and retracted to pass objects close to rails. Plows like this come in all sorts of shapes and sizes as railroads tended to build their own out of freight cars, caboose and tenders. The important thing is they needed to be heavy as hitting a snow bank at speed creates quite an impact as you can see in the video below. (courtesy of James Adeney from You Tube).

But when the snow gets really deep you simply can’t push through so out come the rotarys. At the front, as shown below, is a large rotating cutting face or fan. This breaks the snow down and forces it out a chute on the top. The chute can be angled to the left or right and throws the snow far away from the railroad. (Photo by Alix Gillman and displayed on Railpictures).

The rotarys move much slower than the plows as they cut through but the only limitation is the amount of power to the fan and how much tractive effort is pushing it into the snow. Typically rotarys are not self-propelled, all the power they generate is used to drive the fan, so they will often be seen with several power units pushing from behind. The early rotarys were all steam-powered which gave the added advantage of heat. Not only would the boiler provide steam to drive the fan but also to melt the ice which built up around the front. The steam rotary below, pictured by Brian Snelson on Flicker, was built in 1898 and was used right up until 1968. It’s typical of an early design with a traditional steam engine tender behind for fuel and water.

As these machines were not in constant use, often only used every five to ten years, they were kept in running order but had little need for updating. However as steam started to become obsolete on the class one railroads they started converting them to diesel and electric power. A good example of this is the Southern Pacific with their route over Donner Pass. They converted the actual rotary to electric power. It was also coupled to a spare EMD F7 B unit which had its traction motors removed and all four installed into the rotary to power the fan. The B unit produced the power for the fan motors. A steam generator was also fitted to keep the front clear of ice and supply warmth to the crew. Controls were added so the crew could control the pushing locomotives from up front. In the image below you can see two rotarys and their F7B units, one at each end of some modern locomotives, as they wait for a passenger train to pass. Up in the high mountains of Donner Pass they often worked like this so they could clear snow in both directions continuously. (Photo by Jake Miille Photography)

This photo is accompanied by a short video of the rotarys working on Donner Pass on February 25th, 2017.

Although the Union Pacific Railroad had many steam rotarys over the years purchased from specialist manufacturers, in the late 1950’s and 1960’s they also built some of their own and it’s one of these which I’m creating a model of. As they started from scratch on their new rotarys it was easy to build them just how they wanted.

UP 900080 was constructed in 1958 at the UP Omaha shops. It was built on the frame and rear truck from a retired ex C&O steam tender. It has a 1750hp diesel engine to drive the 12′ rotary fan, weighs 347,240 pounds, is 50′-9″ long and 16′-8″ high. (Photo by Steve Patterson and displayed on Railpictures).

UP 900081 was constructed in 1966 at the UP Omaha shops again on the frame and rear truck from a retired ex C&O steam tender. This time UP put in a 3000 hp diesel engine making this rotary the most powerful and weighing 367,400 pounds also the heaviest rotary in the United States. It is 52′-2″ long, 17′ high and the rotary fan is 12′ in diameter. (Photo by Joe Bracey and displayed on Railpictures).

UP 900082 was constructed in 1971 also at the UP Omaha shops. It has a 2500 hp diesel engine, weighs 284,500 pounds, is 55′-3″ length, 17′ high and has a rotary fan 12′ in diameter. (Photo by Mike Danneman and displayed on Railpictures).

Out of the three 900080 and 900082 are still in service but sadly 900081 was damaged in 1994. UP retired the rotary but donated it to the Museum of Transportation, St. Louis, Missouri later that year where it’s now on display.

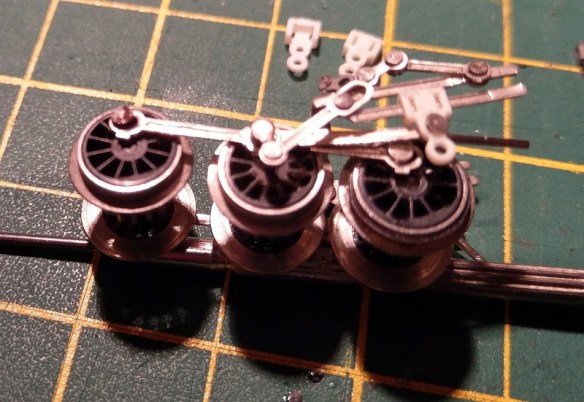

As 900081 was the most powerful, 900082 currently holds that honor, it’s this one which I’m modeling, although it’s very similar to 900082 so it could be used for either. The plan is to have a free rolling chassis but still have a motor inside to power the fan. To do this I will most likely use a commercial chassis from a diesel locomotive and remove the drive gear from the truck towers. Then I’ll connect the drive shaft to the fan. Sounds very similar to what SP did with theirs!

Next week I’ll share with you some of the design drawings and go over some of the finer details I intend for the model. To round-up this week’s post I’ll leave you with two videos of the White Pass & Yukon Railway’s steam rotary plow doing what it does best. (Both courtesy of Murray Lundberg from You Tube).

You must be logged in to post a comment.