I have recently been helping a friend build a large OO Scale layout and one of the questions I’m regularly asked is ‘How do I make a robust and reliable DCC Bus?’ In this post I’ll share with you what I’ve done for him.

For those wondering why we need a DCC Bus or what is a DCC Bus, I will explain. Traditionally model railroads have been powered using DC controllers and control panels with switches to turn sections on and off. The advantage of this is the wire going to each section need only be capable of powering the train in operation. Often telephone exchange wire or simple hook-up wire is used as it is cheap and can handle the low current draw over long distances. However with DCC all of the track is powered at the same time and the more trains you run, the higher the current draw through the wire. Electricity always takes the path of least resistance and this could mean all the power for the layout could end up going down one wire. If a small wire is used this can lead to loss of power or in worst cases, melted wires, which could lead to fire.

There are several ways to resolve this. One option is to solder all the rails together and feed them close to the DCC controller but this leads to problems with expansion and contraction in different times of year. This is not possible with modular layouts and sometimes it’s simply not possible as you need to add breaks at turnouts to prevent shorts.

Another option is to simply use big wires everywhere. However this is very cumbersome, expensive and bulky. Soldering big wires also takes more heat so when it comes to connecting them to the track there’s a bigger risk of meting the plastic ties.

The best option is to have a DCC Bus which consists of a pair of big wires that run around your layout under the base board. Then use small hook-up wire as ‘droppers’ running from the track to the DCC bus. It’s also recommended to have droppers for every section of track; that way you’re not relying on rail joiners to transfer current.

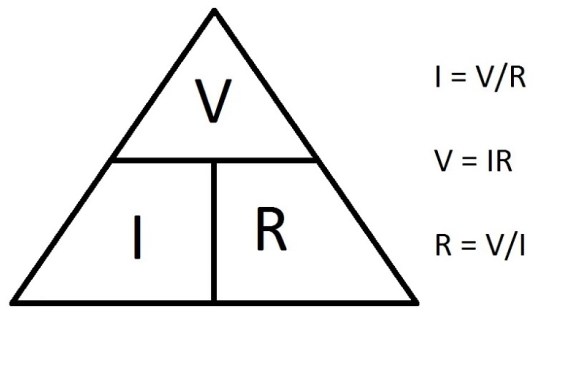

So what actual wire should you use? Well, there’s no specific size but I try to stick to these American Wire Gages and colours.

DC/DCC Bus Red and Black 13 AWG

Track Feeders Red & Black – Under 9 inches 24 AWG

Track Feeders Red & Black – Over 9 inches 20 AWG

Frog Feed (For Turnouts) Green 24 AWG

A 13 AWG wire comes in all sorts of types but I have a good supply of thick six strand cable so that’s what I use. It has good insulation and although flexible it tends to stay where you bend it.

One thing to avoid when making a DCC Bus is to limit the number of breaks and connections in the wire. Breaks can cause resistance and bad electrical transfer. For example, if you are using a high strand count wire and suitcase connectors (which cut into the wire) to join on the feeders; this is a bad idea. At each connection a strand or two is broken and over the length of the cable the integrity can be affected. Also, if the cable is split and joined together again at every feeder location with a chock-block, or similar connector, this can add lots of potential bad connections into the bus.

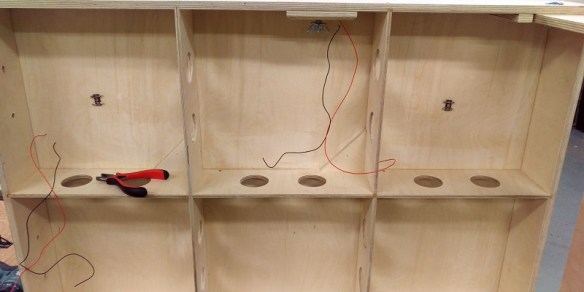

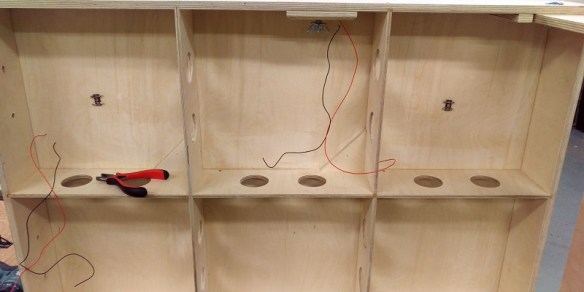

To show you how I avoid all the issues above I’m going to use one of the smaller sections of the layout as an example. Below you can see the underside of the module with the track feeders coming through the board. As the modules are being built away from my friend’s house the DCC Bus will be soldered together once installed. If I was building it in place I would just use a continuous wire.

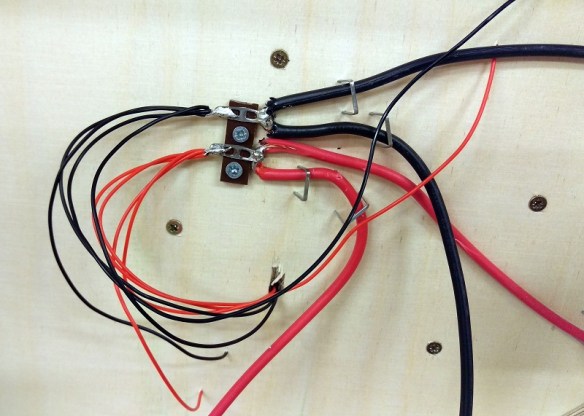

I use Tag Strips, as pictured below. These have been cut into lengths of three strips.

The strips are held in place simply by bent sections of metal and, by squeezing these together with a pair of pliers, the middle strip can be removed.

This allows the section of Tag Strip to be screwed to the underside of the module.

I put a Tag Strip at each end of the module and, as you will see later, at any point where feeders come through the base board.

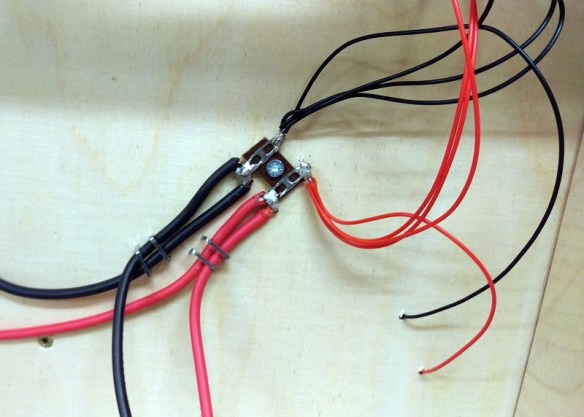

Then I feed the DCC Bus cable through the module and, making sure there’s enough cable to reach the next board, strip back some of the insulation.

Then I wrap about three inches of solder around the bare wire.

The wire is then bent into a U shape.

Then the solder is melted into the wire with the iron. As the wire is thick it takes a lot of heat but leaves the shape solid and the wire is still continuous.

I then tin the Tag Strip and place the soldered U section under the Tag Strip. Then using the iron I heat up the strip and wire so all the solder flows together forming a solid joint.

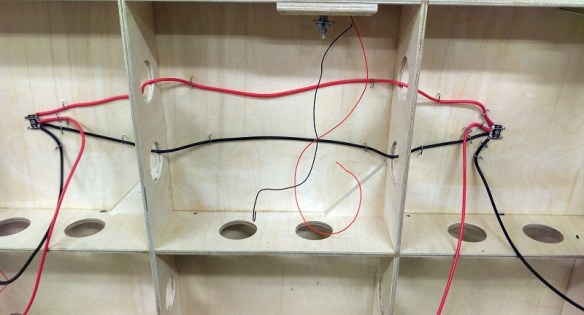

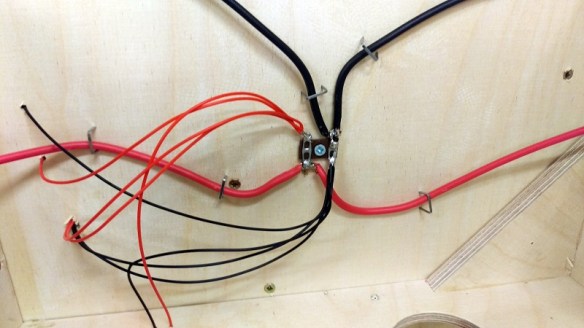

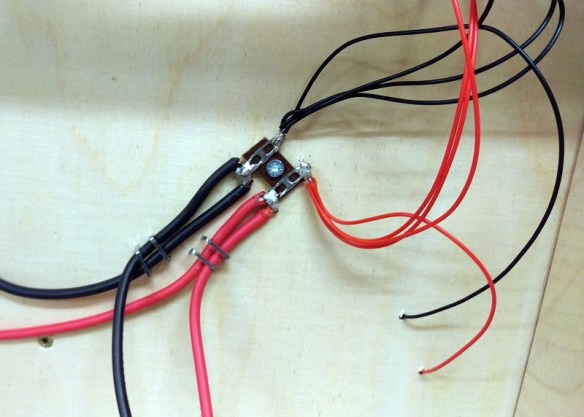

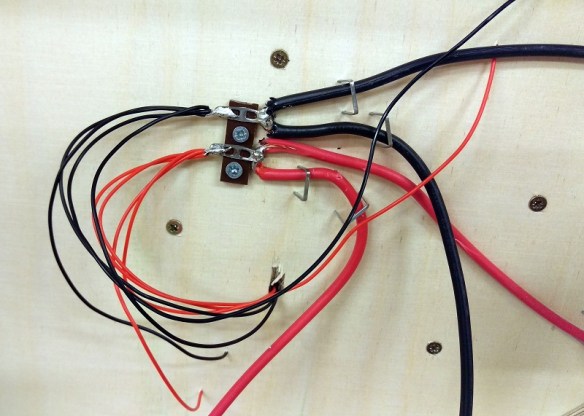

I repeat this with both wires at all Tag Strip locations and staple the wire to the module.

The droppers are then soldered to the other sides of the Tag Strips.

And that completes the DCC Bus under this small board.

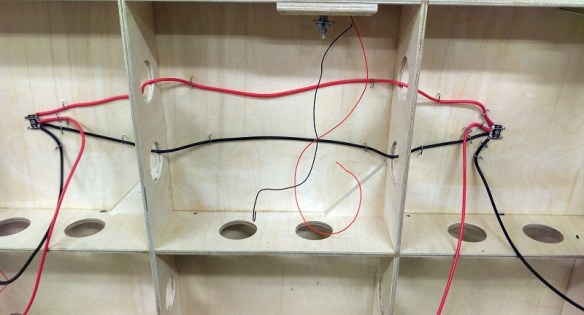

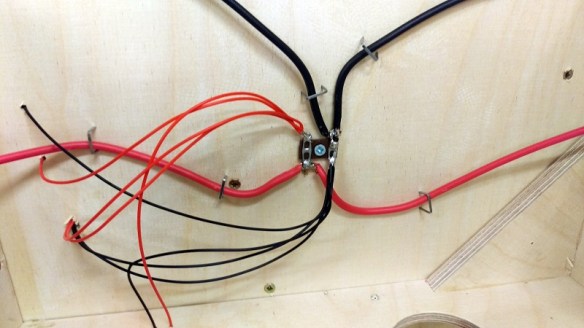

Larger boards with lots more droppers are just as easy with the Tag Strip; connecting them all is simple as you can see below and if more need to be added at a later date they can simply be soldered on.

This board had several Tag Strips in the middle of the board and again the DCC Bus is continuous without any breaks in the wires.

Because the wire is nice and stiff it stays in place and can easily be held there with a few staples. Below is another section of DCC Bus at the end of a module.

I do have a few suggestions that might help when making the DCC Bus:

Each time you connect a set of feeder wires to a Tag Strip use a volt meter to do a continuity check between the red and black wires. That way if a section of track hasn’t been cut properly at a turnout or point or there’s some other short issue it will always be located at the last wire you connected. Otherwise when you finish a whole board and there’s a short it can take ages to find and may end up having to undo all your work.

When you bend the main DCC Bus wire into a U shape, don’t solder the wire first as you won’t be able to bend it.

When you heat up the Tag Strip to connect the DCC Bus wire make sure it’s a good connection and that the solder runs together otherwise you could have a dry joint that will add resistance or lack of connection into the system.

Make sure your droppers are a sensible length, if they’re too short it means you’ll need more Tag Strip locations.

When running the bus wires try to keep them apart by a few inches; this will eliminate any issues caused by induction. This can have tiny effects on the DCC signals.

And lastly, double-check you have enough length at the ends your modules to join the DCC Bus together.

I find by doing all of this I end up with a strong bulletproof wiring system which leads to well running trains.

In next week’s post I will have some more to share with you about my Alco C-855 project.

You must be logged in to post a comment.